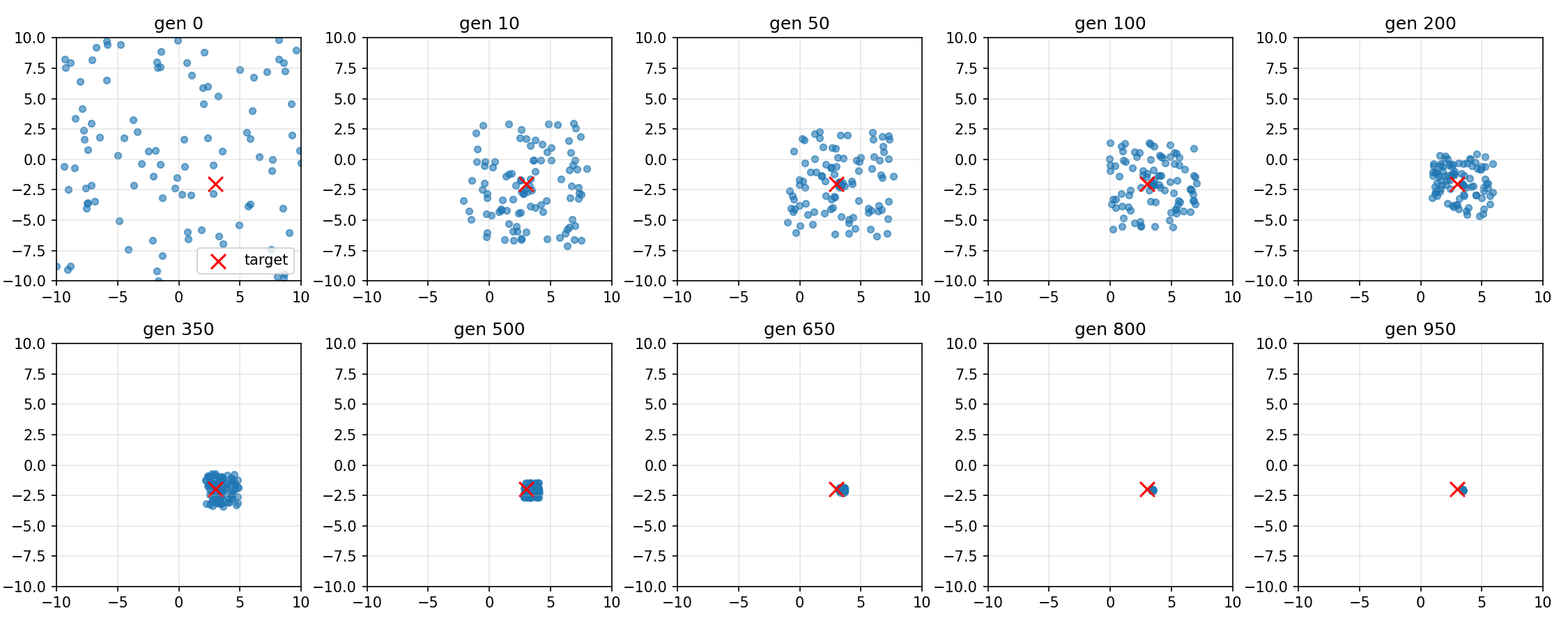

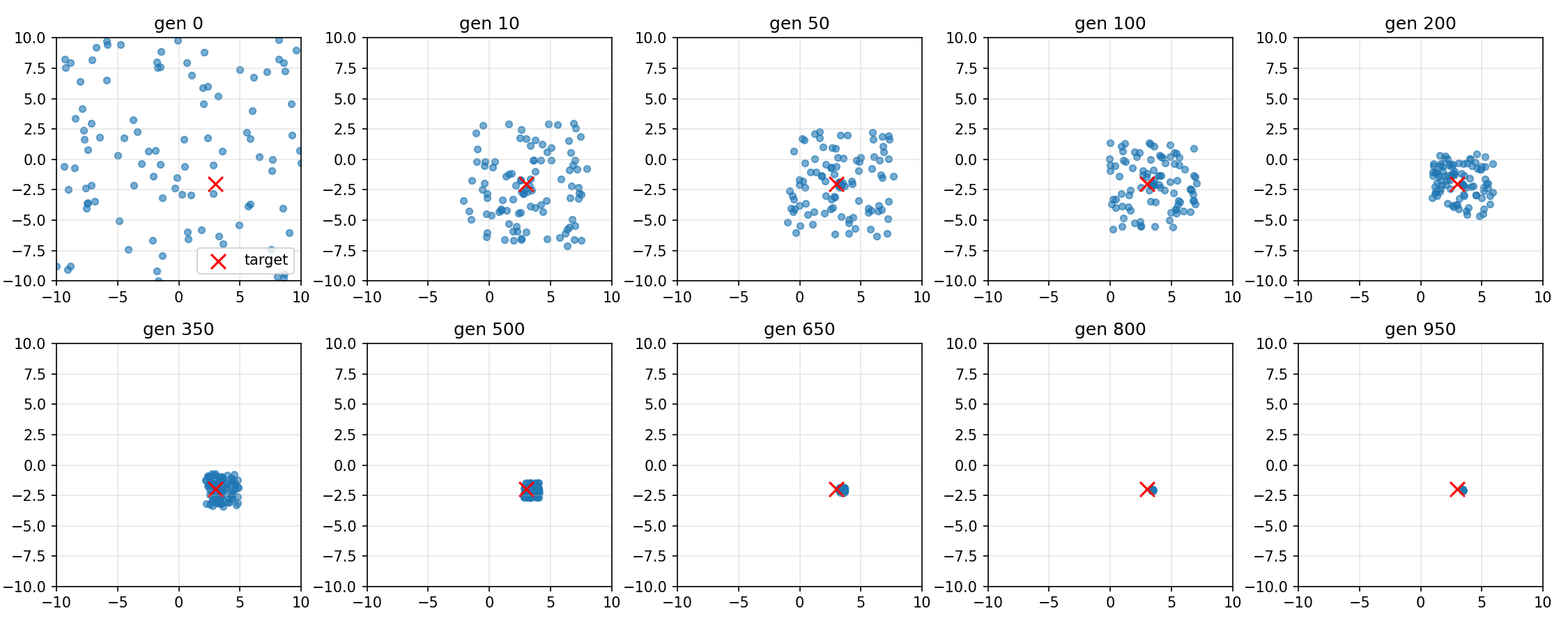

A few generations of a genetic algorithm visualized

A few generations of a genetic algorithm visualizedGenetic algorithms are really cool tools that sound far more complicated than they actually are.

Genetic algorithms find a solution to a problem in a continuous solution range. When you're looking for an input that gives a desired output, genetic algorithms are great tools to get an approximation.

The core idea of a genetic algorithm is to use a shotgun to shoot at a range of possible inputs, see which pellets landed in the spots that give the best results, and try again, but with slightly less dispersion and aimed at the points that landed the best in the first round.

A few generations of a genetic algorithm visualized

A few generations of a genetic algorithm visualized

This is a very simple genetic algorithm that simply optimizes towards the least distance between the point that is an individual and the point (3, -2). This means that each individual in a generation is a set of two floats. The individuals / points that are closest to the target make it to the next generation and "pass on their genes". Variations are created on those points for the following generation and this is repeated 1000 times in this case. The random variations become smaller with the number of generations to find the sweet spot and not hit very wrong points.

import random

import math

def func(x):

return 5 * x**2 + 6 * x + 1

def score(y):

return abs(func(y))

generation = [random.uniform(-10, 10) for _ in range(100)]

generation.sort(key=lambda x: score(x))

reps = 1000

for gen in range(1, reps):

generation.sort(key=lambda x: score(x))

new_gen = []

for i in range(1, 10):

new_gen.append(generation[i])

for _ in range(9):

# mutation_scale = 5 * math.exp(-5 * gen / reps)

mutation_scale = 5 * (1 - gen/reps)**3

# new_gen.append(generation[i] + random.uniform(-1, 1) * 5 * math.log(reps - gen))

new_gen.append(generation[i] + random.uniform(-1, 1) * mutation_scale)

# new_gen.append(generation[i] + random.uniform(-1, 1) * (100 / (gen + 100)))

generation = new_gen

generation.sort(key=lambda x: score(x))

print(generation[:2])

print(func(generation[0]))

Now let's go through it step by step:

The main loop:

And that's it, really. We repeat this many times and random individuals are replaced with highly performant ones. With each generation, the top individual converges towards a value that gives the desired output of f(x).

The mutation scale is the amount of variation or mutation that a "child" individual has from its "parent". The higher it is, the more the new individual will vary from the individual it was created from. We want this value to stay relatively high initially to see the whole range of solutions and to avoid being trapped in a saddle, but we also want it to decrease with time to find precise answers that are truly the best individuals instead of jumping around towards random values.

The mutation scale can be calculated in many ways and the best probably depends on the application, but after having experimented with a few ways of calculating it, I settled on $5 * (1 - gen/reps)**3$. Gen refers to the index of the current generation, and reps refers to the number of generations that will exist with time. Gen varies from 0 to reps as the program runs. this means that $(1 - gen/reps)$ will go from 1 to 0 linearly. Cubing this makes mutation scale start at 5 and then decrease rapidly.

Conditions: 1000 repetitions,

Output: -0.19999999999395845

Error: 2.4166224577015782e-11

When applying the quadratic formula, we can calculate the real solutions as -1 and -0.2. The genetic algorithm found a solution with an error of less than $10^{-11}$ which is quite impressive knowing that the algorithm knows nothing of the quadratic formula. Genetic algorithms can give extremely precise solutions without knowing anything about the problem itself.

Another problem that we could solve with genetic algorithms are exponential forms like the one bellow.

def func(x):

return math.exp(x) - x**2 - 5

These simple examples aren't where genetic algorithms shine. While writing this post, I came across Newton's method, which would be far more efficient than genetic algorithms on these problems. This makes this post semi-useless, but I still find it pretty cool that with a couple of lines of code, you can find solutions to a huge range of problems with incredible precision. You just need to change the return line of the function definition or the score function to get results to difficult problems.